Posted on October 10, 2020 at 11:21 pm

That year, Bill Clinton was the president, and he was younger than I am now.

That year, there was only one show eligible for the Best Score Tony, and so it went to Sunset Blvd. by default.

That year, the legendary George Abbott died.

Unrelated: Dua Lipa was born.

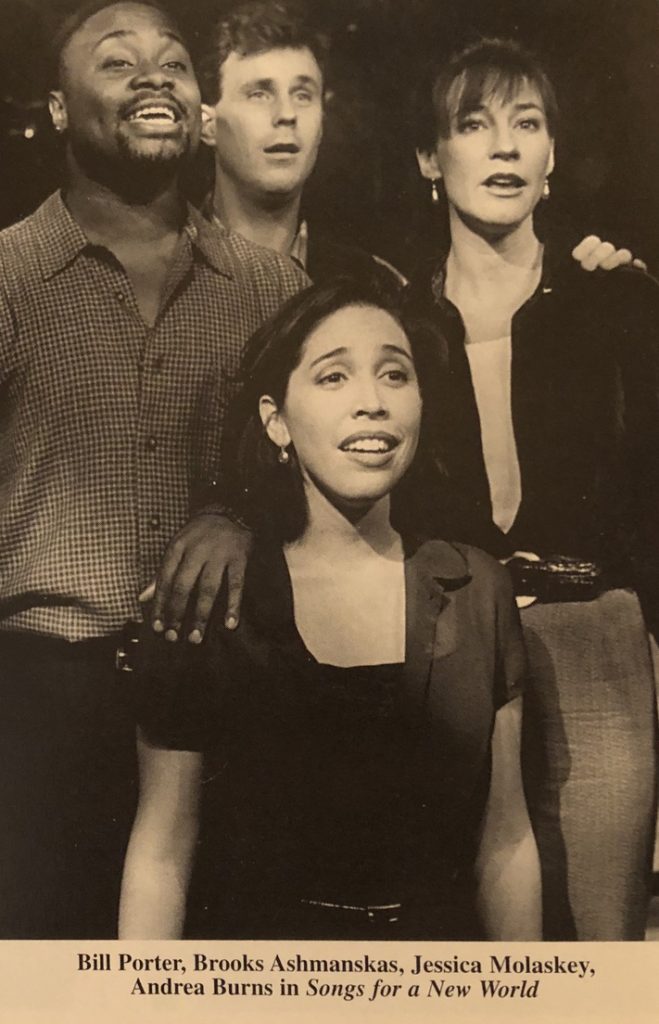

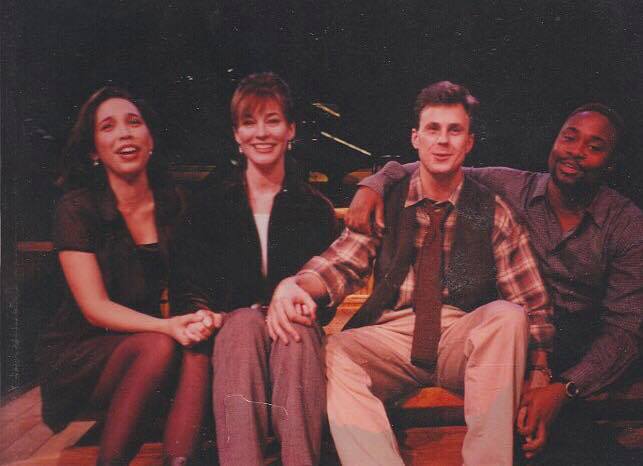

As of that year, Andréa, who I’d met at summer camp when I was twelve years old, had not yet done a Broadway show (she’s now done seven). Neither had Brooks (he’s now done fourteen). Molaskey was still seven years away from recording her first album. And eighteen years would pass before Kinky Boots turned Billy into the hardest- and longest-working overnight sensation any of us ever knew.

Oh, and that year, one afternoon, we stopped tech rehearsal mid-day and gathered around a television that had been set up awkwardly on top of a file cabinet so we could watch the O.J. Simpson verdict. I remember us all wandering around the theater in silence for the next hour, unsure of what to say or to feel. The world was dancing.

I probably have a hundred stories that I regularly tell about that first production of Songs for a New World in 1995 – have I told you about when Elaine Stritch showed up for a matinee and was one of only about fifteen people in the audience? or when Andrew Lloyd Webber left after Act 1? or when the percussionist forgot to bring his sheet music to the stage with him after intermission? or the closing night, after the audience had left, when I played the first songs from Parade for the cast?

Or did I mention the part where Daisy sat with me for four years, building this show, massaging and rearranging and conceiving and tearing apart and microscopically examining and encouraging and bullying and loving and insisting and listening and being the best collaborator I’ve ever had? I don’t know if I mentioned that part.

All that said, this is the thing I wanted to show you:

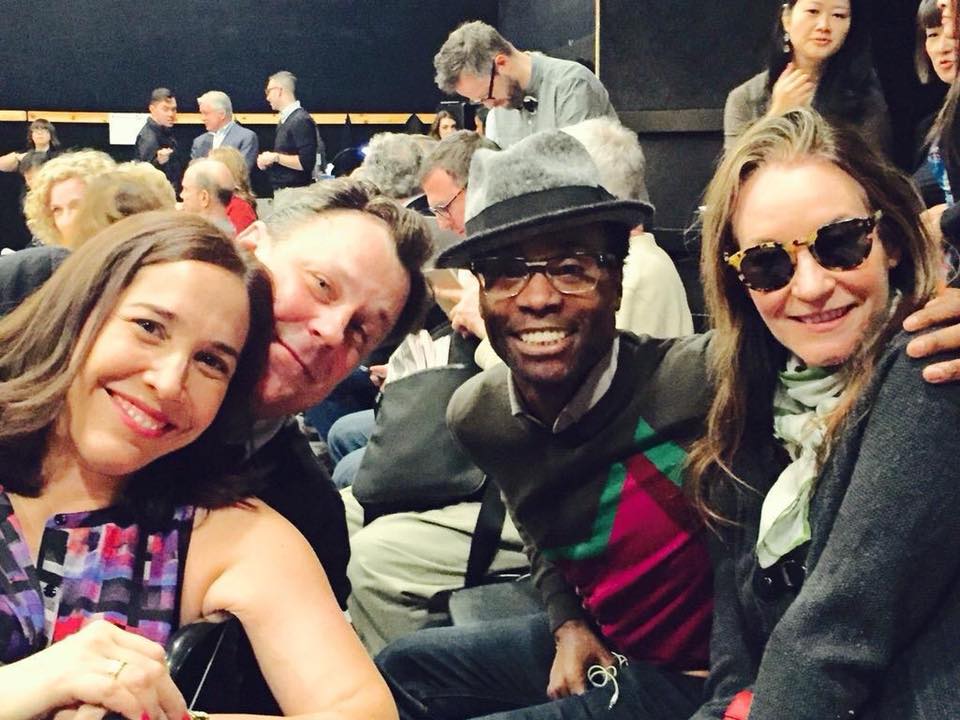

Those pictures were taken twenty-two years apart, and those four people are still my friends, my collaborators, my lifeline, as they are to each other, as we all are to Daisy Prince, our fearless leader, our visionary. They helped give birth to the show that, more than any other, continues to bring my music into the world.

(There are a lot of pictures of me and Daisy together, but this is the one that I think really defines us.)

Kyle Renick ran the WPA Theater, and he had hired me in 1994 to be the musical director for a musical by Yoko Ono, which was truly one of the weirdest things I’ve ever done. Perhaps to show his gratitude for what I endured during that process, he agreed to let me and Daisy put up our show at his theater. I can’t tell you enough what that means. Someone actually said yes, someone committed resources – and most importantly, a slot in their season – to two people who did not have a single professional credit between them. Because of Kyle, an audience was able to walk into a theater and see this show. I did not know at the time how rare that was in New York City. I think it is even rarer now. In fact, I know it is. You should know about Kyle – he should always be part of this story.

In 1995, the reviews were generally dismissive, but the one I like most, even with all its equivocations, is Clive Barnes from the New York Post. Of all the critics, ol’ cranky Clive was the one who took my work seriously, and I have to give him credit for that – almost no one in this business then or now takes the work of 25-year-old songwriters seriously. So, catching up, twenty-five years later: there have been more than 500 productions of this show since then, in dozens of languages. When we did a production at City Center two years ago, the shows were sold out and there were literally lines down the block, 2700 people at every performance who knew every word. We were not a hit in 1995, but in its own quiet and insistent way, Songs for a New World has become a significant vital part of the vocabulary of musical theater. My entire career stands on the back of this show. I never stop being amazed at that.

This year, a pandemic.

This year, a reckoning with the corrosive destructive effects of white supremacy.

This year, the first time in history that Broadway has ever been completely shut down.

And today, on the 25th anniversary of the opening of the original production of Songs for a New World, a new production of the show is opening at the London Palladium, one of the only live theatrical productions going on anywhere on Earth right now. That is the most powerful tribute to this show’s effect that I could imagine.

I was talking to the director of that new production the other day, and he said, Isn’t it astonishing how the show seems to speak to this moment in time? And I sort of dismissed it – it’s the kind of thing you say to the composer of the old show you’re directing – but you know what? It is kind of astonishing. I wrote these songs at the beginning of an era of real liberal progress in this country, a time when those of us in the theater world were all optimistic that America was improving and dealing with its past. To hear it now, in this moment of crisis, of division, is to hear all the rage that was hiding underneath the surface optimism. Some of the reviews from 1995 talk about that “hopefulness” as being cheesy, clichéd. It didn’t feel that way to me then, and it certainly doesn’t now. The moment you think you know where you stand, the things that you’re sure of slip from your hand. This song was made for the times when you don’t know where to go. It’s the one thing I have that has never let me down.

—

From 1994, a demo of the finale, “Hear My Song,” including the Final Transition, recorded by Andréa Burns, Amy Ryder, Billy Porter and Brian d’Arcy James.

2 comments

That show reached me in ways I didn’t fully understand until I matured a little bit more. Thank you for putting it into the world. In each turn of my life, a different lyric has caught me, almost stopped me breathless in a moment to rethink its meaning. And, yes, I have found myself listening to that album more frequently during this pandemic, separated by too much distance from the ones I love.

Thank you for this back story. For your art.

I am happy to learn more about the genesis of this wonderful revue/show. Also it is somehow reassuring to read that the initial reviews were mixed — and that not all performances were sold out. Hurrah for its ongoing life…as well as the ongoing creative lives of the folks who made it happen in the first place!

The comments are closed.