Posted on August 25, 2009 at 10:41 pm

R. M. Kennedy asks:

I’m going to be playing the piano in an upcoming production of Last Five Years, and I have a few questions. First, in No. 3 [See I’m Smiling], you mark that two passages are to be “vamped,” under spoken text. In the first instance, the bar after the vamp (“…I think we both can…”) forms the end of a phrase, but if the instructions are followed, there will be an odd number of bars in the phrase. Should I jump on the first bar of the vamp to even out the break, or should it be odd? Before the “rant scene,” there is another vamp followed by a 1/4 bar. Should I jump on the third beat of the second bar, or should the last bar be as a 5/4? Also, in No. 4 [Moving Too Fast], you mark several chords with “fall-off.” Does that signify a glissando, or something else? I’ve never ventured out of classical repertoire before, so that direction is unfamiliar. I would appreciate help.

And JRB responds:

Thanks so much for writing, and best of luck on playing the show! If you’ve never played gospel-style piano, and you’ve never played musical theater, The Last Five Years is certainly going to be a challenge. But I’ve heard a lot of pianists rise to the task of bringing this score to life, and I do think all the sweating and cursing is worth it. The pianist in this show is as much an actor in the play as the two lead performers, and the amount of discipline and energy required to get through a performance is rather greater than most other musicals.

Let’s look at the three places you asked about, one at a time:

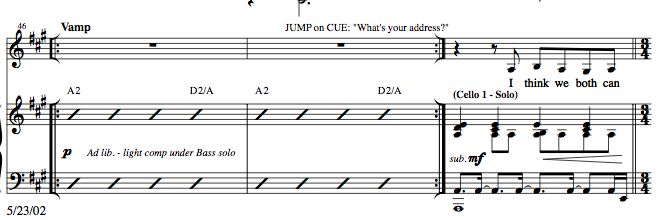

Ex. 1:

If you’ve only ever played classical repertoire in your life, this probably looks like a lot of hieroglyphics. Measures 46 and 47 are marked as a “VAMP.” That means that they are to be repeated until the conductor (which, in this case, is probably also the pianist) gives the cue to move on. But the key to your question is the marking above measure 47: “JUMP on CUE.”

The reason I gave that instruction is that I wanted as little time as possible to elapse between Jamie saying “What’s your address?” and Kathy singing “I think we both can see what could be better.” If that “JUMP” instruction weren’t there and you heard Jamie say his line while you were in the middle of bar 46, you would be stuck playing the rest of that measure and the whole next one before you could get out of the vamp – six beats during which the actors have nothing to do and there’s nothing interesting happening musically. Therefore, as soon as you hear the cue, you JUMP to measure 48.

The questioner above, however, is asking a more nuanced question: If you play the whole vamp and then play measure 48, you’ll end up playing an uneven phrase. It’s sort of unmusical, and any pianist worth their salt is going to resist being unmusical in that way, just instinctively. Here’s how you deal with that problem: you don’t. The audience isn’t paying attention to the phrase lengths, they’re paying attention to the story, and if you get stuck in a vamp, you’re stopping the story from going on. I’m grateful and appreciative of the fact that good pianists don’t want to let things become unmusical in the process of playing a show, but the drama wins. Especially in this case when the music is really just a groove with a bass solo going on. So when you hear Jamie’s cue, you should JUMP on the next downbeat to measure 48. It may even be appropriate to jump on beat 3, in the middle of a measure – I certainly did that a couple of times during the run of the show in New York. It becomes a question of taste and comfort. If you think the band is ready to follow you, and you’re ready to throw the cue, then throw it. I wouldn’t, however, recommend jumping on beat 2 or 4; there is a limit to how unmusical you can be. (Wait for the next example.)

Other pianists might well be wondering what those slashes are in the piano part – after all, if it’s a piano part, shouldn’t there be notes for the pianist to play? The slashes indicate that the pianist is to make up his or her own part in that measure. (Each slash represents a beat of music – since this section is in 4/4, there are four slashes in each bar.) There are two pieces of information included to guide the pianist on how to make that part up:

The CHORDS written above the staff explain what the harmonic makeup of that measure will be. The fact that there’s a different chord written over the fourth slash means that the chord changes on the fourth beat. Any musical theater pianist should know how to read chord symbols, it’s an essential part of the gig. Some chord symbols can get aggressively arcane, like a F7+(#11), and some composers use different symbols than others – in this case, an A2 means that there’s an added second in the chord (a B natural). Sometimes this replaces the third, sometimes it doesn’t – that becomes a matter of taste.

The word COMP says that this section is not meant to be a SOLO. “Comping” means just playing a groove, something that supports a soloist harmonically without drawing attention to itself. Here, you’re supporting a bass solo, and that’s happening under dialogue, so it’s all gotta be pretty low-key.

Why didn’t I just write out a piano part for those two measures? Because the vamp goes on for rather a long time (about a minute, if I recall correctly) and it would get distracting for the audience to hear the same exact pattern repeated for a full minute – the slashes give the pianist permission to alter the pattern and improvise some ideas (lightly and tastefully!). It’s also a lot less boring for the player.

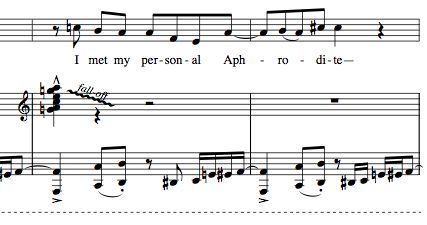

Ex. 2:

Okay, this all looks pretty familiar from the last example. The only difference is that wacky 1/4 bar that you have to jump to. The reason I wrote it like this is that the music in that 1/4 bar is an important transition into the next section, and that transition has to happen in exactly that amount of time and no longer. If I had written it as a 4/4 bar and just put that transition on the last beat, you’d have to sit for three beats of not-very-important music just to get to the gesture I need. Therefore, what I’ve written is for the pianist to sit in the vamp until you hear the cue and then JUMP right to a 1/4 bar. Again, the question above is about whether it should be unmusical. Do you jump on beat 4 and make the measure sound like a 4/4 bar (and therefore comfortably musical) or do you just jump wherever and grit your teeth through the weird feeling that you’ve added or subtracted a beat of music?

Again, the drama wins – jump as soon as you hear that cue. When I was conducting the show, that cue came on every possible beat over the course of the run; the band was always ready to jump to it whenever I threw the cue. It’s great having a band that’s flexible and comfortable enough to do that; if you’re a little less secure, I’d suggest throwing the cue on beat 2 or 4 and making it feel even. But no matter how gifted you are, don’t try to do it on the eighth notes in between!

Ex. 3:

I had an idea years ago to write a guide to my particular style of playing the piano, explaining all the thumb runs, rolloffs, finger slides, aleatoric fills, the crazy crap that comes perfectly naturally to me and feels to most other pianists like abuse. I never did get around to writing that guide, but maybe this is the first chapter.

Fall-offs are a pretty standard tool in a jazz or gospel player’s repertoire. Basically, it’s a fast glissando. The notation is a little misleading, however – almost anyone is going to do that gliss with their thumb, which means that the fall-off comes from the lowest pitch in the chord, not the top. In this specific fall-off, here’s what I do:

On the beat, I hit the chord – my thumb is hitting both the G and the A. Almost immediately, my thumb and my second finger BOTH start downward glissandi. My thumb will ultimately make it about an octave down – the second finger will have lifted off by then. As the name suggests, there is a natural diminuendo that takes place – by no means would I accent the end of a fall-off. This all happens very quickly – my hand is off the piano by the second eighth-note of the beat. A fall-off should feel sort of like a sigh, or maybe a shout. There are exceptions, but they’re usually marked as such: “Long fall-off” or something like that. I’ll write that for a horn player, but I don’t think I’ve written it for a pianist.

Okay, that was officially the wonkiest entry in the history of this blog. I hope it wasn’t too patronizing. Anyone who’s read this far, please feel free to ask further questions about how to play my piano parts accurately – it’s always good to find out what other pianists consider difficult in my work.

We’re currently working on a re-design of this whole site to make it easier to navigate, but in the meantime, there are some other wonky pianist questions answered in this entry and especially this one, so feel free to dig around the archives and see what you can find.

5 comments

Thanks for that article! I’m the resident MD for the Cumberland County Playhouse and in my 11 years of being an MD, I basically had to figure all of the hieroglyphics out on my own. It’s very refreshing to read a musical theater article geared toward pianists. Thanks again!

The Last 5 Years is by far the most challenging, fun, and rewarding show I’ve ever played. I always enjoy your tips. And you should still write that book… maybe with a different title, though. 🙂

I wish you wrote a book on how to play any kind of Jazz Gospel Piano. I taught myself how to play chord charts and I love playing your material. I practice daily trying to get each measure as accurate as possible. Just in case a friend asks if I can play something of yours (which most people can not), I can at least show my friend what most of it will sound like. Studying your writing skills has helped me so much in sight reading all other kinds of music because your chords and rhythms are so challenging. I still can’t sight-read Sondheim very well. Nothing can really help me there. But honestly thank you so much for the tips.

I cannot play piano (or anything else for that matter) so this was flying quite peacefully over my head…until my 10-year-old son (who does play) walked in and looked at the screen, saw the notes displayed…looked closer, and went…”Cool!”

Then, of course, he left the room and went back to goofing off until bedtime…

Still, something in there he thought was “cool” which, to me, is pretty cool! Thanks for the great, VERY informative post!

Mr. Brown! Wikipedia says a 13 national tour is being considered! Is this true, or as of right now should we just be on the lookout for Regional productions?!

[FROM JRB: Oh, Christ, Wikipedia could make me lose my mind. No, there’s no national tour being considered, unless it’s being considered by someone who hasn’t mentioned it to me. The show is now available for general licensing all over the planet Earth.]

The comments are closed.