Posted on October 31, 2012 at 10:28 pm

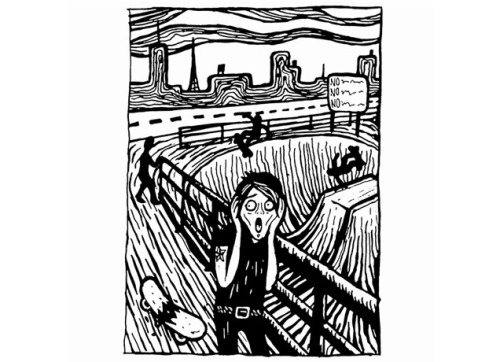

Since the dawn of time, Man has told tales of horror and devastation. Perhaps they serve as a warning. Perhaps they draw a community together. Or maybe people just have a collective need to scream in terror. I know this: these stories are borne of our deepest fears, our most devastating shames and humiliations. This is my story. It is all true. Horribly true.

In order to tell this story, I have to hide someone’s identity. He was my best friend back then. I myself have shown a surprising willingness over the years to demonstrate and recount my own stupidity, but this person has been understandably more reluctant to do so. Nonetheless, he is part of the story and it can’t be told without him, so I’ll refer to him by an alias: He shall be known as Franz Liszt.

OK, here goes. It’s 1993. I’m 23 years old. All I dream about is writing for the musical theatre. I have been dreaming of it for 10 years, nonstop, and it is because of the work of Stephen Sondheim. Had it not been for Sweeney Todd and Sunday in the Park With George, I would have probably joined a rock band and tried to be Billy Joel. But once I heard what could be done, what enormous musical and emotional potential could be unleashed, I knew I had to write musicals. To say I’m a Sondheim Worshiper is to understate the case considerably — I owe my ambition and my dreams to him. Without his example, I wouldn’t even know who to become.

By this time, I’ve met Steve (can I call him Steve?) a couple of times, primarily because of my relationship with Daisy Prince, and he’s always been perfectly cordial, but I’m still utterly intimidated by him and, having been told of his withering wit, I’m wary of engaging too much with him for fear of being eviscerated by some casual sarcasm. I don’t want to come off like some teenage musical theatre geek, but honestly, I sort of am a teenage musical theatre geek and I know how uncool that is. So I keep my distance.

Franz is not as sheepish as I. He’s a little older, but he’s also devastatingly charming, impossibly talented, and confident that he can guide any conversation safely to shore. I occasionally refer to him as “The Waring Blender” because he is so smooth.

So Franz writes Steve a letter. Something like: I’m an aspiring composer and I would love to show you the work I do, casual but focused, chummy but respectful. To our collective shock, Steve writes back. AND: he invites Franz over to his place, to the House of Stephen Sondheim, so that Franz can show him what he’s been working on. I’m paralyzed with jealousy, but Franz has clearly won this round; I don’t want to seem like a copycat by writing my own letter (and oh God, what if he doesn’t invite me to his place?), so there’s not much to do but wait for the inevitable story of Franz’s Visit to The Oracle in Turtle Bay.

The day comes, I sit around miserably pretending I’m not sitting around waiting to hear what happened. Finally the phone rings. Franz is bubbling with excitement, and I don’t even remember what he told me about the lunch or the house or anything because he has some extremely important news: Knowing that Franz and I are such good friends, Steve has invited us, both of us, to go see his newest show, his treat, and then have dinner with him afterwards. Much squealing and giddiness, much counting of our lucky stars.

Oh, if only we had known.

The night comes, Franz and I take our seats, and we notice that sitting right behind us is Frank Rich, the chief theatre critic for The New York Times. Do you see the stars aligning against us? We chose to go on the very same night that the Times came to review the show. The most important night in the life of any show in New York City.

The curtain rises, and we expect to see Sweeney Todd. We expect West Side Story. We expect Biblical greatness. There is no show on Earth that could have delivered something as magnificent as we were expecting. Two-and-a-half hours later, Franz and I file out of the theatre anxiously.

We get to the restaurant. Steve is sitting there waiting for us. There’s an appetizer already on the table. I am about to sit down with my idol, Stephen Sondheim, for dinner. I’m 23 years old. I’m totally overwhelmed.

We say nothing. I mean, small talk, yeah, sure, and pleasantries. But we don’t even mention the show. For TWENTY MINUTES. Steve is sitting across from us, becoming ever more uncomfortable and upset, and Franz and I are nattering on like the hosts of a morning talk show, oh the weather, the food, the décor, what shows are coming in this season, anything except the performance we just saw. On the night that Frank Rich came.

Finally, after an eternity, Steve mumbles, “So, uh, did you like the show?”

Here’s where you scream in terror.

Actually, however, the blood is already on the wall. It didn’t matter at that point what we said, the damage had been done. Our silence had told the story with astonishing completeness.

It is only now, on the cusp of my 40th birthday, that I understand what power young people have. They know something that we’ve lost somehow — we want the approval of our peers, yes, but the generations coming next, these children, those are the people whose approval we truly need if our lives are to mean anything, if our art is not to have been in vain. It had never occurred to me that Steve invited us to see his show because he wanted our approval. I couldn’t have understood that at 23 years old. If I had, I would have just told Stephen Sondheim how lucky I felt that I lived in a world that had been changed by his art.

The rest of dinner went pretty much as you’d expect; many extremely awkward silences punctuated by bursts of frantic, desperate conversation about anything other than the slaughtered elephant in the middle of the room, and finally, a confused and relieved parting.

Franz and I knew it had been a disaster. Immediately upon returning home, I called Daisy to ask for her advice. What could be done to repair the damage?

A council was immediately convened of Daisy’s family and myself. It was determined and arranged that I should call Steve the next day at his house in Connecticut, that I should be appropriately humble and abashed, and that I should be prepared to hear some harsh words of wisdom. It was also made clear that I should not expect this particular wound to heal easily or quickly.

So I called Steve the next day. It was not a fun phone call. He was clearly still hurt, but he acknowledged at one point that “that’s exactly the kind of stupid thing I would have done at your age.” Which I appreciated.

And then Steve said something which I have never forgotten, and I will paraphrase it here so that it may serve as a lesson to all, a lesson learned by me at the foot of the master:

Nobody cares what you think. Once a creation has been put into the world, you have only one responsibility to its creator: be supportive. Support is not about showing how clever you are, how observant of some flaw, how incisive in your criticism. There are other people whose job it is to guide the creation, to make it work, to make it live; either they did their job or they didn’t. But that is not your problem.

If you come to my show and you see me afterwards, say only this: “I loved it.” It doesn’t matter if that’s what you really felt. What I need at that moment is to know that you care enough about me and the work I do to tell me that you loved it, not “in spite of its flaws”, not “even though everyone else seems to have a problem with it,” but simply, plainly, “I loved it.” If you can’t say that, don’t come backstage, don’t find me in the lobby, don’t lean over the pit to see me. Just go home, and either write me a nice email or don’t. Say all the catty, bitchy things you want to your friend, your neighbor, the Internet.

Maybe next week, maybe next year, maybe someday down the line, I’ll be ready to hear what you have to say, but that moment, that face-to-face moment after I have unveiled some part of my soul, however small, to you; that is the most vulnerable moment in any artist’s life. If I beg you, plead with you to tell me what you really thought, what you actually, honestly, totally believed, then you must tell me, “I loved it.” That moment must be respected.

It’s a shame I had to learn that lesson in front of the person whose approval I desired most in the world. It’s a shame that I was robbed of a friendship with Steve for many years because of my youthful arrogance. But ultimately the wound healed, in its way, and I’ve had enough putzes come up to me to share their completely unwanted opinion of my own work that I think it must be some kind of karmic payback.

It’s an ugly story, yes, but I tell it here because, in spite of its humiliations and horrors, that evening of dreadful mistakes gave me one more reason to be thankful for Stephen Sondheim: I could have spent an entire life worshiping at his altar and never understanding that such great art as he creates can only be borne of deep vulnerability. I have allowed myself to feel and embrace my own vulnerability ever since. The village is safe again. The sun has risen. Our heroes go into the new world, bloodied, changed forever. End of story.

Originally published in the Summer 2010 issue of The Sondheim Review, a periodical of great taste and discernment.

41 comments

This is a great story. And a lesson well-worth sharing. Thank you, Jason.

Wow. I’d have died. Melted down, right there, and died.

But then, I’d feel the same if I had done that to/with Stephen Sondheim, Stephen Schwartz or yes, even JRB.

I loved this story! Thanks for sharing…

PS I actually loved this story!

Very brave of you, Bravo. I hope Mr. C sees the post, he may be you at this very moment! Thanks for understanding.

It takes a certain superhuman strength and bravery to show us your soft underbelly. I love your soft underbelly. I love it with all my heart.

Now, now, Helene, let’s not get randy.

Truly, a wonderful story. I’m sorry to put it like that, because I see how painful it was to go through! But a real lesson in grace, and the folly of being young, and the wisdom gained only through experience (or reading Jason Robert Brown’s blog.) thank you!

Wow, that was truly humbling and extremely true, all of it! I’ve never heard what you put in the “paraphrased bit” said so bluntly, and I’d always underestimated those precise moments after a show… but it totally makes sense. Thank you so much, I learned a lot reading that.

We artists, so vulnerable, out of one thousand positive comments, we will remember the one not so positive comment that we believe is the “real truth.”

This just happened to me and because of this one persons not so positive comment to one of my friends about my performance after the Ms. Senior America preliminary, I was given the opportunity to be one of the top ten and sang like theres no tomorrow, not since my Juilliard days, knocked it out of the park and won the crown. Jason, know that you are sooo loved and respected by every singer and voice teacher I know. You are a brilliant composer and pianist. Not since Sondheim has there been anyone that I respect so much. Sometimes young people want to impress and show thr master how much they know, never even suspecting the master might be so vulnerable and sensitive. We should all be aware of how our comments can affect a performer. Thanks for the lesson allwe ask need

Brilliant story, brilliantly and emotionally told. The first time I worked with the Master was at La Jolla when he and James Lapine were re-doing “Merrily We Roll Along.” I never realized how much support and reassurance the greatest man of theater needed — his humility was truthful and unnerving. He does not know how much I owe him. His suggestions to my wife after FOLLIES (2001) closed on Broadway that I do something that I love (teaching) and his recommendation letter gave me a happier life. == Larry Raiken

So, my mama was right: “If you don’t have anything nice to say (“I loved it!”), don’t say anything.” Thanks for sharing this tale, Jason. As a theatre reviewer, I am always concerned that I may hurt someone with my criticism of their work. I don’t believe that credibility has to go hand in hand with cruelty nor that integrity demands invectives.

He did you a favor, and realized that he had the opportunity to, because you did something right: you asked a trusted friend, how to fix something you felt you’d gotten wrong. Then you followed that advice and got to the well for a bit of hard-earned wisdom.

If you printed this out and dropped it into the mail with a card attached, “Steve – Thanks for that lesson,” you might find that he had forgiven you by the end of that phone call.

I’ll bet he did, or he wouldn’t have taken the time to teach the lesson.

I did almost the exact same thing also at 23 with Merrily We Roll Along. It took me many years to recover too, and I do okay in theater now (not as a writer though). Steve even came to my 40th birthday party, but I too learned: “no unasked for criticism”.

Thank you, Jason.

This is a great story, and a great lesson.

As a 46 year-old theater guy, I have done all of this and worse. Sadly, I don’t have youthful ignorance as an excuse.

Your words apply equally to all of the arts; and remind us that human empathy, compassion, and the ability to support one another are often more important than a critic’s keen eye or a razor-sharp wit.

Thank you.

I remember you telling me this story years ago…

So what, exactly, DID you say about the show?

Thanks for sharing this fantastic story. We seem to learn so much more easily through pain than through joy. If sex hurt that much, think how much smarter we’d all be! Thanks for distilling your life lesson down so eloquently, so we can all benefit from your hard-earned wisdom. And – I so enjoyed working on the workshop of your show with you and Daisy. Hope all’s going well. You are incredible.

Thanks for the painful reminder that there is a time and a place for everything. A review, for example, is NOT the same as a personal comment. It is public, not private. Reviews should be honest, yet, one hopes, constructive and not at all cruel. I have also had friends ask both in the development process and after a show closed to critique the show, and there I think you owe it to them to be honest about the strengths and weaknesses of a script or performance if you remember to stress both. But when you see someone after a show, “I loved it,” “You were terrific,” etc. are the only responses. Period.

I wish I had read this story when I was 19 – it would’ve saved me a solid 5 or 6 years of being an insufferable prick.

Wonderful, wonderful story! Thank you for sharing and reminding us all that what we do is delicate and a piece of ourselves. Just Beautiful!

Ha! Love it!!

Unsettling that I, unknown to you, should be haunted by ghosts of your past. Ignoring, distracting, and avoiding failed. I know you only in song, one in particular, a song of resurrection. A New World quieted my soul, silently screaming, alone but for a positive diagnosis. I loved it–for its comfort, for existing, for as long as I should live. As a former performer, I prided myself on the integrity of silence when “I loved it” rang false. As a blogging theatre critic, I prided myself on the integrity of reporting with the same brutal wit and biting snark with which I spoke to friends–effusive in love, eviscerating in hate, emotionless in cruelty. How simple the lesson of kindness. So simple, I had learned it before in the words of Linda Eller, who said to her son as he tentatively, on wobbly legs, left the house for his first dance, “Do the kind thing. You can never go wrong doing the kind thing.” Will the ravenous, Tourettian bitch rant hateful in the privacy of friends? Absolutely. She is the star of brunches, expected to go on. But I will stop my public slaughter–out of respect for you and your story, my hero Stephen Sondheim, and the frailty of the artists’ spirit. I thank you for the haunting. I am most hopefully changed, and I love it.

You would not go to a person’s house for dinner and critique the meal. It’s just rude. I’ve been saying this for years and I’m always shocked by the number of actors who say, “Oh, I can’t lie.” Yes you can.

Thank you, JRB. Wonderful, wonderful story.

Wonderful in its youthful sincerity and wonderful in its “been-on-both-sides-of-that-coin” feelings in me.

From the timeline you’ve provided I am guessing the show was “Passion” in which case, I too have a few “notes.”

Just kidding–“I loved it!”

It wasn’t “Passion”!

Dang! This was well worth reading. A valuable lesson and an obvious one. All the best lessons are. Wish I had learned it earlier. Glad I got to it now and not on my deathbed. Scratch that one off the list!

Kindness and support can go a long way, even with legends. The legend in question, Stephen Sondheim, by the way, is one of the kindest and most supportive men in the theater.

Good story, but it could have been better. I thought the second act was particularly slow.

;P

(srsly, thx for sharing sir)

Jason, thanks so much for sharing this story. My only experience (so far) meeting Mr Sondheim was after having written him and asked him out to lunch when he was on a visit with Mr Rich to my undergrad school. He wrote me back himself and politely declined my invitation; after all, this was his 80th birthday year and he had been very busy, not to mention he had been having some health issues around that time. I did, however, get the opportunity to sit in on a small-group Q&A with him, and the experience was transformative for me because I got to see him finally as a human being.

As I’ve been getting my feet on the ground in the city, it’s been important for me to have my idols humanized for me. We can idolize and fantasize but until we recognize that core humanness in these people, we can’t be truly and honestly grateful for their contributions, much less join in the task of making new work. And saying, “I loved it” doesn’t have to be dishonest, either; this work takes balls and persistence and blood, and when I am supporting a friend, there is always a very true “I loved it” to the experience–even if we come from a different stylistic or ideological place, I am grateful to have been included in the developmental phase and honored to have been trusted with that person in his/her most vulnerable state.

I used to think I was immune to friends’ reactions; recently, however, a good friend of mine accompanied me to an open mic, and afterward told me she thinks I’m a bad lyricist, my voice is nothing special, and she has no idea why I’m doing this at all. I admired her for being a “straight shooter” at the time, but it’ll come as no surprise to you that we’re no longer friends, for this and many other reasons that all stem from a profound lack of generosity of spirit.

We are weak when our heart is in our work and we bare it for people whose opinions we trust. And there is no shame at all in being vulnerable in that way; in fact, I think it’s the most important thing. There is dignity and quiet strength to putting ourselves out there and hoping that our friends share the common experience of joy in making new work. We are all in this together.

I had a somewhat different reaction to this story. First, let me say that my own experience with Sondheim showed him to be amazingly kind and generous, and my admiration for him goes back to before most people ever heard of him. Having said that, it seems to me that if you invite two people to your show and to meet you for dinner afterward, you have to be prepared for their honest reaction; particularly when you ask “Did you like it?” If you are THAT sensitive about it, don’t put yourself in a position to be hurt! Personally, I would far rather hear a critique than some phony “support,” which I’m not going to believe anyway. But there you are: I’m such an arrogant ass that no one’s opinion really matters to me but my own.

Great story, and thanks for sharing. If he wanted your approval though, as you say, then to be offended that its not the reaction he was after is senseless. As an artist, even though obviously i’d want to get great feedback, it really means nothing to me if its not honest.

Well then, I wonder why Mr. Sondheim felt it necessary to trash a beautiful and innovative production like “Porgy And Bess” in the New York Times… I think he might have forgotten his to heed his own advice…

Thank you for your honesty and bravery in sharing this story. The lesson truly hit home. You were kind to my high school student and me when I wrote some years ago to ask for the music to “Surabaya Santa” (before it was published). She deeply wanted to sing it. We got the music from you & she performed it very very well. Thank you again for your music and your wisdom.

I remember this incident so clearly, if only because you and “Franz” told it to me at the Pump House restaurant in Hackettstown the night of your performance. If memory serves, Sondheim at one point simply left the restaurant leaving you and Franz there. I also seem to remember that “Franz” felt the bulk of the assault on Steve was from you and your “honest critique” while he sat there like a deer in headlights. It is still one of my favorite stories. I’ve actually used this story as an example for what young actors should not do if invited to a performance. Safe to say you both (actually all three) recovered from the incident and done rather well.

I’m not surprised that that was how Franz characterized it!

Great essay, Jason. Thanks for your insight, and willingness to share.

“Loved it!”

The only other Sondheim show it could have been (provided the story is factual, and if not, then why believe a word of it, anyway?) is “Putting it Together.”

What great advice. I’ve always believed as well that there is no point in giving criticism to something that has already been created. What good would it do? Support is everything. He’s a smart guy, that Stevie.

I think you’re being too hard on yourself. And a tad disingenuous. You weren’t his dear friend; you’d never even met him prior to the show. And Mr. Sondheim’s cautionary note expressed to you the following day — as paraphrased by you — is puzzling.

If he felt that vulnerable on opening night (and who could blame him?), then it would be up to him to ensure that he surrounded himself with lifelong friends, lovers, proven sycophants, etc. … as opposed to two strangers. Surely Mr. Sondheim, beloved musical theater icon since the 1950s, doesn’t have to search high and low to find acquaintances to share his dinner table. Unless he suffers from intolerable table manners (i.e., drooling, spitting out chicken bones, wiping his face on his guests’ sleeves, etc.), the list of viable candidates must go on for miles. As for the fact that you think it was the opinion of a young person that drove his decision, again, I find it impossible to imagine that Mr. Sondheim can’t rustle up a few good young men who he counts on as friends.

By inviting unknowns to his table, and not throwing out any clues as to the expected behavior, he was the one who acted foolishly. Not you. That said, next time I find myself in the situation to support a dear friend at a critical moment, I will do just that.

Reminds me of the time — I was VERY young, too — Giuseppe Verdi sent me a seat to the world premiere of his new opera, Falstaff. This was in 1893. He was almost eighty. He was a multi-millionaire. He had nothing to lose. And you know the story, of course — they unhitched the horses of his carriage and drew him through the streets from La Scala to his hotel. (No one has ever done this for Sondheim, but — no matter.) Total triumph! Then we went in to dinner. And I hadn’t liked it. I mean, Falstaff is nothing like any earlier Verdi opera. ANY. It’s totally different. And I didn’t like it. I didn’t know what to say. “Gee, it’s no Trovatore, is it, Maestro?” I merely mumbled. La Strepponi kicked me under the table with her silken slipper. I still couldn’t think of a thing to say. The Italian language had gone completely out of my head. Bestia, dude!

Of course, the Maestro never lost his sense of humor. Marvelous man. As I was leaving, head sunk between my shoulders like something Othello describes to Desdemona, he spoke over my head to the flunky at the door. “Just chop his head off at the first landing,” he said. I took off running and was halfway to Gorgonzola before you could count ten.

What a guy.

Great story. Umm… so, I’m an aspiring composer (seriously). How ’bout lunch?

Trackbacks

The comments are closed.