Posted on August 27, 2014 at 1:51 am

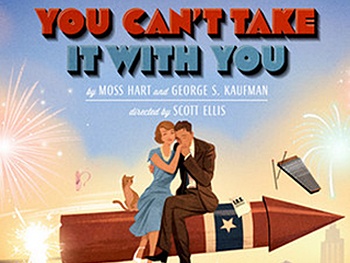

Kaufman and Hart’s wonderful comedy You Can’t Take It With You won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1937 and has been a staple of theaters all across America ever since. A new production started previews tonight on Broadway, starring James Earl Jones, Elizabeth Ashley and Kristine Nielsen, and I was lucky enough to write the incidental music.

Ted Sod interviewed me about my score for the play earlier this month for the Roundabout Theatre Company blog, so now you can read all about my history with the Vanderhof clan, including the rather surprising role that I played in a production in 1983 at French Woods.

TED SOD: Where were you born and educated? What made you decide to write music and lyrics for the theatre?

JRB: I was born in Tarrytown, NY and grew up in Rockland County. I spent two festive if not entirely fruitful years at the Eastman School of Music before dropping out to teach in Miami. I started writing music when I was seven or eight years old, and from the outset, my work always tended toward the dramatic. Writing for the theatre was a natural outgrowth of the kind of music I was writing anyway, which I suppose had been influenced equally by Billy Joel and Carole King on the one side and Leonard Bernstein and George Gershwin on the other.

TED SOD: How did you get involved writing original music for You Can’t Take It With You? Does the play have personal resonance for you and if so, how?

JRB: When I saw the announcement that this production was going to happen, I did something entirely uncharacteristic of me: I wrote Scott Ellis an email and told him how much I loved this play and wanted to be a part of it. Apparently, nobody involved sounded alarm bells quickly enough so here I am. I have a deep affection for the work of Kaufman and Hart, and You Can’t Take It With You in particular. I must have watched my videotape of the Jason Robards telecast about two hundred times; even now, when I read the script, I hear George Rose’s and Colleen Dewhurst’s line readings. I actually performed in the show when I was maybe thirteen at summer camp – the cringeworthy fact is that I played Donald, the boyfriend of the maid, Rheba, played in that production by future animation voiceover superstar Nika Futterman. As good liberal East Coast Jews, Nika and I of course felt uncomfortable pretending to be black people, so in a fit of inspiration, we decided that we would instead play Donald and Rheba as Mexicans. I reiterate that I was thirteen years old and this kind of logic is not inconsistent with the mind of a 13-year-old boy. I don’t know what excuse Nika will have. Tragically, I don’t think we got many laughs either, but that may have been because of the incomprehensibility of our ludicrous Castillian accents.

TED SOD: What is the first thing you have to do in order to write original music for a play? What kind of research do you have to do in order to write it? Can you give us some insight into your process?

JRB: So much about writing music is intuitive for me. Once I know who the characters are and the setting of the piece, a sound has already emerged in my head. In this case, the Depression-era New York setting and the loving and anarchic sensibilities of the Vanderhofs immediately suggested the music of Raymond Scott (who most folks will probably associate with “Powerhouse” and other songs used ad nauseam in Bugs Bunny cartoons). One of my favorite recordings on Earth was a CD by Don Byron called “Bug Music” (Nonesuch), where he and a group of otherworldly musicians recreated – and elaborated on – original Raymond Scott recordings, as well as some Duke Ellington and John Kirby. That music is imprinted on my brain, so I’m just playing with music in that style for this production.

TED SOD: Having written both music and lyrics for musicals on Broadway, what is the most challenging part of writing original music for an existing play? What part is the most fun?

JRB: The most fun for me of any process is always getting the musicians together. For this show, I’m assembling a group of amazing jazz players who are going to show up in a studio for a couple of hours and blow their brains out, and I get to play with them. Nothing’s better than that, as far as I’m concerned. Everything leading up to that is kind of torture, especially writing orchestrations, which I do with the relative speed and enthusiasm of ritual slaughter, but it’s all worth it for the chance to make music with musicians I love and respect.

TED SOD: How will you be collaborating with director Scott Ellis?

JRB: Scott and I had a meeting a couple of weeks ago to discuss where he thought music should happen in the play and what the basic feel of that music should be. Once I have my themes and cues written, I’ll wander over to rehearsal and show them to him, and then we’ll just bounce ideas off of each other and shave off time in some places and add time in others. Jon Weston, our sound designer, will also have a part in the process, since he’ll help edit the recordings and determine the volume and exact placement of the cues.

TED SOD: Will your score for You Can’t Take It With You be played live or recorded? What kind of instrumentation will there be? Where will the score be recorded? Will you conduct and arrange it yourself?

JRB: As of this writing, things are still somewhat in flux, but I’m pretty sure there’s an eight-piece band: piano, bass, guitar, drums, clarinet, sax, trumpet and maybe accordion. [Note: I ended up skipping the accordion.] Nothing would make me happier than to have the score performed live every night, but alas, that is a very expensive proposition and it ain’t my money. So sometime before tech starts, all the musicians will gather in some hovel in midtown Manhattan and record the score, and that’s what the audience will hear every night.

—

—

The amazing musicians on the You Can’t Take It With You recordings are:

Robert DeBellis, clarinet

Sal Spicola, tenor sax/bass clarinet

Tony Kadleck, trumpet

Randy Landau, bass

Stephen Benson, guitar

Benny Koonyevsky, drums

JRB, piano

The sessions were recorded and mixed by Jeffrey Lesser at John Kilgore Sound & Recording in Manhattan on August 19, 2014.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

The comments are closed.